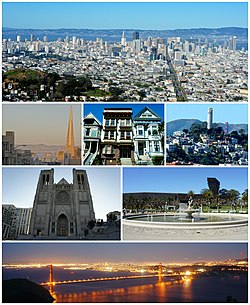

San Francisco /sæn frənˈsɪskoʊ/, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the cultural, commercial and financial center of Northern California.

The only consolidated city-county in California, San Francisco encompasses a land area of about 46.9 square miles (121 km2) on the northern end of the San Francisco Peninsula, giving it a density of about 17,867 people per square mile (6,898 people per km2). It is the most densely settled large city (population greater than 200,000) in the state of California and the second-most densely populated major city in the United States after New York City. San Francisco is the fourth-most populous city in California, after Los Angeles, San Diego and San Jose, and the 14th-most populous city in the United Statesâ€"with a Census-estimated 2013 population of 837,442. The city and its surroundings are known as the San Francisco Bay Area, part of the San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland combined statistical area, with a population of 8.5 million.

San Francisco (Spanish for "Saint Francis") was founded on June 29, 1776, when colonists from Spain established a fort at the Golden Gate and a mission named for St. Francis of Assisi a few miles away. The California Gold Rush of 1849 brought rapid growth, making it the largest city on the West Coast at the time. Due to the growth of its population, San Francisco became a consolidated city-county in 1856. After three-quarters of the city was destroyed by the 1906 earthquake and fire, San Francisco was quickly rebuilt, hosting the Panama-Pacific International Exposition nine years later. During World War II, San Francisco was the port of embarkation for service members shipping out to the Pacific Theater. After the war, the confluence of returning servicemen, massive immigration, liberalizing attitudes, along with the rise of the "hippie" counterculture, the Sexual Revolution, the Peace Movement growing from opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War, and other factors led to the Summer of Love and the gay rights movement, cementing San Francisco as a center of liberal activism in the United States.

San Francisco is a popular tourist destination, known for its cool summers, fog, steep rolling hills, eclectic mix of architecture, and landmarks including the Golden Gate Bridge, cable cars, the former prison on Alcatraz Island, and its Chinatown district. San Francisco is also the headquarters of five major banking institutions and various other companies such as the Gap Inc., Pacific Gas and Electric Company, Yelp, Pinterest, Twitter, Uber, Mozilla and Craigslist.

History

The earliest archaeological evidence of human habitation of the territory of the city of San Francisco dates to 3000 BC. The Yelamu group of the Ohlone people resided in a few small villages when an overland Spanish exploration party, led by Don Gaspar de Portolà arrived on November 2, 1769, the first documented European visit to San Francisco Bay. Seven years later, on March 28, 1776, the Spanish established the Presidio of San Francisco, followed by a mission, Mission San Francisco de AsÃs (Mission Dolores), established by the Spanish explorer Juan Bautista de Anza.

Upon independence from Spain in 1821, the area became part of Mexico. Under Mexican rule, the mission system gradually ended, and its lands became privatized. In 1835, Englishman William Richardson erected the first independent homestead, near a boat anchorage around what is today Portsmouth Square. Together with Alcalde Francisco de Haro, he laid out a street plan for the expanded settlement, and the town, named Yerba Buena, began to attract American settlers. Commodore John D. Sloat claimed California for the United States on July 7, 1846, during the Mexican-American War, and Captain John B. Montgomery arrived to claim Yerba Buena two days later. Yerba Buena was renamed San Francisco on January 30 of the next year, and Mexico officially ceded the territory to the United States at the end of the war. Despite its attractive location as a port and naval base, San Francisco was still a small settlement with inhospitable geography.

The California Gold Rush brought a flood of treasure seekers. With their sourdough bread in tow, prospectors accumulated in San Francisco over rival Benicia, raising the population from 1,000 in 1848 to 25,000 by December 1849. The promise of fabulous riches was so strong that crews on arriving vessels deserted and rushed off to the gold fields, leaving behind a forest of masts in San Francisco harbor. California was quickly granted statehood, and the U.S. military built Fort Point at the Golden Gate and a fort on Alcatraz Island to secure the San Francisco Bay. Silver discoveries, including the Comstock Lode in 1859, further drove rapid population growth. With hordes of fortune seekers streaming through the city, lawlessness was common, and the Barbary Coast section of town gained notoriety as a haven for criminals, prostitution, and gambling.

Entrepreneurs sought to capitalize on the wealth generated by the Gold Rush. Early winners were the banking industry, with the founding of Wells Fargo in 1852 and the Bank of California in 1864. Development of the Port of San Francisco and the establishment in 1869 of overland access to the Eastern U.S. rail system via the newly completed Pacific Railroad (the construction of which the city only reluctantly helped support) helped make the Bay Area a center for trade. Catering to the needs and tastes of the growing population, Levi Strauss opened a dry goods business and Domingo Ghirardelli began manufacturing chocolate. Immigrant laborers made the city a polyglot culture, with Chinese railroad workers creating the city's Chinatown quarter. In 1870, Asians made up 8% of the population. The first cable cars carried San Franciscans up Clay Street in 1873. The city's sea of Victorian houses began to take shape, and civic leaders campaigned for a spacious public park, resulting in plans for Golden Gate Park. San Franciscans built schools, churches, theaters, and all the hallmarks of civic life. The Presidio developed into the most important American military installation on the Pacific coast. By 1890, San Francisco's population approached 300,000, making it the eighth-largest city in the U.S. at the time. Around 1901, San Francisco was a major city known for its flamboyant style, stately hotels, ostentatious mansions on Nob Hill, and a thriving arts scene. The first North American plague epidemic was the San Francisco plague of 1900â€"1904.

At 5:12Â am on April 18, 1906, a major earthquake struck San Francisco and northern California. As buildings collapsed from the shaking, ruptured gas lines ignited fires that spread across the city and burned out of control for several days. With water mains out of service, the Presidio Artillery Corps attempted to contain the inferno by dynamiting blocks of buildings to create firebreaks. More than three-quarters of the city lay in ruins, including almost all of the downtown core. Contemporary accounts reported that 498 people lost their lives, though modern estimates put the number in the several thousands. More than half of the city's population of 400,000 was left homeless. Refugees settled temporarily in makeshift tent villages in Golden Gate Park, the Presidio, on the beaches, and elsewhere. Many fled permanently to the East Bay.

Rebuilding was rapid and performed on a grand scale. Rejecting calls to completely remake the street grid, San Franciscans opted for speed. Amadeo Giannini's Bank of Italy, later to become Bank of America, provided loans for many of those whose livelihoods had been devastated. The influential San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association or SPUR was founded in 1910 to address the quality of housing after the earthquake. The earthquake hastened development of western neighborhoods that survived the fire, including Pacific Heights, where many of the city's wealthy rebuilt their homes. In turn, the destroyed mansions of Nob Hill became grand hotels. City Hall rose again in splendorous Beaux Arts style, and the city celebrated its rebirth at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915.

It was during this period San Francisco built some of its most important infrastructure. Civil Engineer Michael O'Shaughnessy was hired by San Francisco Mayor James Rolph as chief engineer for the city in September 1912 to supervise the construction of the Twin Peaks Reservoir, the Stockton Street Tunnel, the Twin Peaks Tunnel, the San Francisco Municipal Railway, the Auxiliary Water Supply System, and new sewers. San Francisco's streetcar system, of which the J, K, L, M, and N lines survive today, was pushed to completion by O'Shaughnessy between 1915 and 1927. It was the O'Shaughnessy Dam, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, and Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct that would have the largest effect on San Francisco. An abundant water supply enabled San Francisco to develop into the city it has become today.

In ensuing years, the city solidified its standing as a financial capital; in the wake of the 1929 stock market crash, not a single San Francisco-based bank failed. Indeed, it was at the height of the Great Depression that San Francisco undertook two great civil engineering projects, simultaneously constructing the San Francisco â€" Oakland Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge, completing them in 1936 and 1937 respectively. It was in this period that the island of Alcatraz, a former military stockade, began its service as a federal maximum security prison, housing notorious inmates such as Al Capone, and Robert Franklin Stroud, The Birdman of Alcatraz. San Francisco later celebrated its regained grandeur with a World's Fair, the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939â€"40, creating Treasure Island in the middle of the bay to house it.

During World War II, the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard became a hub of activity, and Fort Mason became the primary port of embarkation for service members shipping out to the Pacific Theater of Operations. The explosion of jobs drew many people, especially African Americans from the South, to the area. After the end of the war, many military personnel returning from service abroad and civilians who had originally come to work decided to stay. The UN Charter creating the UN was drafted and signed in San Francisco in 1945 and, in 1951, the Treaty of San Francisco officially ended the war with Japan.

Urban planning projects in the 1950s and 1960s involved widespread destruction and redevelopment of west-side neighborhoods and the construction of new freeways, of which only a series of short segments were built before being halted by citizen-led opposition. The onset of containerization made San Francisco's small piers obsolete, and cargo activity moved to the larger Port of Oakland. The city began to lose industrial jobs and turned to tourism as the most important segment of its economy. The suburbs experienced rapid growth, and San Francisco underwent significant demographic change, as large segments of the white population left the city, supplanted by an increasing wave of immigration from Asia and Latin America. From 1950 to 1980, the city lost over 10 percent of its population.

Over this period, San Francisco became a magnet for America's counterculture. Beat Generation writers fueled the San Francisco Renaissance and centered on the North Beach neighborhood in the 1950s. Hippies flocked to Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s, reaching a peak with the 1967 Summer of Love. In 1974, the Zebra murders left at least 16 people dead. In the 1970s, the city became a center of the gay rights movement, with the emergence of The Castro as an urban gay village, the election of Harvey Milk to the Board of Supervisors, and his assassination, along with that of Mayor George Moscone, in 1978.

Bank of America completed 555 California Street in 1969 and the Transamerica Pyramid was completed in 1972, igniting a wave of "Manhattanization" that lasted until the late 1980s, a period of extensive high-rise development downtown. The 1980s also saw a dramatic increase in the number of homeless people in the city, an issue that remains today, despite many attempts to address it. The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake caused destruction and loss of life throughout the Bay Area. In San Francisco, the quake severely damaged structures in the Marina and South of Market districts and precipitated the demolition of the damaged Embarcadero Freeway and much of the damaged Central Freeway, allowing the city to reclaim its historic downtown The Embarcadero waterfront and revitalizing the Hayes Valley neighborhood.

The last 20 years have seen two booms driven by the internet industry. First was the dot-com boom of the late 1990s, startup companies invigorated the San Francisco economy. Large numbers of entrepreneurs and computer application developers moved into the city, followed by marketing, design, and sales professionals, changing the social landscape as once-poorer neighborhoods became increasingly gentrified. Demand for new housing and office space ignited a second wave of high-rise development, this time South of Market. By 2000, the city's population reached new highs, surpassing the previous record set in 1950. When the bubble burst in 2001, many of these companies folded and their employees were laid off. Yet high technology and entrepreneurship remain mainstays of the San Francisco economy. By the mid 2000s, the social media boom had begun, with San Francisco becoming a popular location for tech offices and a popular place to live for people employed in Silicon Valley companies such as Google.

Geography

San Francisco is located on the West Coast of the United States at the north end of the San Francisco Peninsula and includes significant stretches of the Pacific Ocean and San Francisco Bay within its boundaries. Several picturesque islandsâ€"Alcatraz, Treasure Island and the adjacent Yerba Buena Island, and small portions of Alameda Island, Red Rock Island, and Angel Islandâ€"are part of the city. Also included are the uninhabited Farallon Islands, 27 miles (43 km) offshore in the Pacific Ocean. The mainland within the city limits roughly forms a "seven-by-seven-mile square," a common local colloquialism referring to the city's shape, though its total area, including water, is nearly 232 square miles (600 km2).

There are more than 50 hills within city limits. Some neighborhoods are named after the hill on which they are situated, including Nob Hill, Potrero Hill, and Russian Hill. Near the geographic center of the city, southwest of the downtown area, are a series of less densely populated hills. Twin Peaks, a pair of hills forming one of the city's highest points, forms a popular overlook spot. San Francisco's tallest hill, Mount Davidson, is 925 feet (282Â m) high and is capped with a 103-foot (31Â m) tall cross built in 1934. Dominating this area is Sutro Tower, a large red and white radio and television transmission tower.

The nearby San Andreas and Hayward Faults are responsible for much earthquake activity, although neither physically passes through the city itself. The San Andreas Fault caused the earthquakes in 1906 and 1989. Minor earthquakes occur on a regular basis. The threat of major earthquakes plays a large role in the city's infrastructure development. The city constructed an auxiliary water supply system and has repeatedly upgraded its building codes, requiring retrofits for older buildings and higher engineering standards for new construction. However, there are still thousands of smaller buildings that remain vulnerable to quake damage.

San Francisco's shoreline has grown beyond its natural limits. Entire neighborhoods such as the Marina, Mission Bay, and Hunters Point, as well as large sections of the Embarcadero, sit on areas of landfill. Treasure Island was constructed from material dredged from the bay as well as material resulting from tunneling through Yerba Buena Island during the construction of the Bay Bridge. Such land tends to be unstable during earthquakes. The resulting liquefaction causes extensive damage to property built upon it, as was evidenced in the Marina district during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Most of the city's natural watercourses, such as Islais Creek and Mission Creek, have been culverted and built over, although the Public Utilities Commission is studying proposals to daylight or restore some creeks.

Cityscape

Neighborhoods

The historic center of San Francisco is the northeast quadrant of the city anchored by Market Street and the waterfront. It is here that the Financial District is centered, with Union Square, the principal shopping and hotel district, nearby. Cable cars carry riders up steep inclines to the summit of Nob Hill, once the home of the city's business tycoons, and down to the waterfront tourist attractions of Fisherman's Wharf, and Pier 39, where many restaurants feature Dungeness crab from a still-active fishing industry. Also in this quadrant are Russian Hill, a residential neighborhood with the famously crooked Lombard Street; North Beach, the city's Little Italy and the former center of the Beat Generation; and Telegraph Hill, which features Coit Tower. Between Russian Hill and North Beach is San Francisco's Chinatown, the oldest Chinatown in North America. The South of Market, which was once San Francisco's industrial core, has seen significant redevelopment following the addition of AT&T Park and an infusion of startup companies. New skyscrapers, live-work lofts, and condominiums dot the area. Further development is taking place just to the south in Mission Bay, a former railyard now anchored by a second campus of the University of California, San Francisco.

West of downtown, across Van Ness Avenue, lies the large Western Addition neighborhood, which became established with a large African American population after World War II. The Western Addition is usually divided into smaller neighborhoods including Hayes Valley, the Fillmore, and Japantown, which was once the largest Japantown in North America but suffered when its Japanese American residents were forcibly removed and interned during World War II. The Western Addition survived the 1906 earthquake with its Victorians largely intact, including the famous "Painted Ladies", standing alongside Alamo Square. To the south, near the geographic center of the city is Haight-Ashbury, famously associated with 1960s hippie culture. The Haight is now home to some expensive boutiques and a few controversial chain stores, although it still retains some bohemian character. North of the Western Addition is Pacific Heights, a wealthy neighborhood that features the mansions built by the San Francisco business elite in the wake of the 1906 earthquake. Directly north of Pacific Heights facing the waterfront is the Marina, a neighborhood popular with young professionals that was largely built on reclaimed land from the Bay.

In the south-east quadrant of the city is the Mission Districtâ€"populated in the 19th century by Californios and working-class immigrants from Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Scandinavia. In the 1910s, a wave of Central American immigrants settled in the Mission and, in the 1950s, immigrants from Mexico began to predominate. In recent years, gentrification has changed the demographics of parts of the Mission from Latino, to twenty-something professionals. Noe Valley to the southwest and Bernal Heights to the south are both increasingly popular among young families with children. East of the Mission is the Potrero Hill neighborhood, a mostly residential neighborhood that features sweeping views of downtown San Francisco. West of the Mission, the area historically known as Eureka Valley, now popularly called the Castro, was once a working-class Scandinavian and Irish area. It has become North America's first and best known gay village, and is now the center of gay life in the city. Located near the city's southern border, the Excelsior District is one of the most ethnically diverse neighborhoods in San Francisco. The predominately African American Bayview-Hunters Point in the far southeast corner of the city is one of the poorest neighborhoods and suffers from a high rate of crime, though the area has been the focus of several revitalizing and controversial urban renewal projects.

The construction of the Twin Peaks Tunnel in 1918 connected southwest neighborhoods to downtown via streetcar, hastening the development of West Portal, and nearby affluent Forest Hill and St. Francis Wood. Further west, stretching all the way to the Pacific Ocean and north to Golden Gate Park lies the vast Sunset District, a large middle class area with a predominantly Asian population. The northwestern quadrant of the city contains the Richmond, also a mostly middle-class neighborhood north of Golden Gate Park, home to immigrants from other parts of Asia as well as many Russian and Ukrainian immigrants. Together, these areas are known as The Avenues. These two districts are each sometimes further divided into two regions: the Outer Richmond and Outer Sunset can refer to the more western portions of their respective district and the Inner Richmond and Inner Sunset can refer to the more eastern portions.

Climate

A popular quote incorrectly attributed to Mark Twain is "The coldest winter I ever spent was a summer in San Francisco." San Francisco's climate is characteristic of the cool-summer Mediterranean climate (Csb) of California’s coast, "generally characterized by moist mild winters and dry summers". Since it is surrounded on three sides by water, San Francisco's weather is strongly influenced by the cool currents of the Pacific Ocean, which moderate temperature swings and produce a remarkably mild year-round climate with little seasonal temperature variation.

Among major U.S. cities, San Francisco has the coldest daily mean, maximum, and minimum temperatures for June, July, and August. During the summer, rising hot air in California's interior valleys creates a low pressure area that draws winds from the North Pacific High through the Golden Gate, which creates the city's characteristic cool winds and fog. The fog is less pronounced in eastern neighborhoods and during the late summer and early fall, which is the warmest time of the year.

Because of its sharp topography and maritime influences, San Francisco exhibits a multitude of distinct microclimates. The high hills in the geographic center of the city are responsible for a 20% variance in annual rainfall between different parts of the city. They also protect neighborhoods directly to their east ("banana belts" such as Noe Valley) from the foggy and sometimes very cold and windy conditions experienced in the Sunset District; for those who live on the eastern side of the city, San Francisco is sunnier, with an average of 260 clear days, and only 105 cloudy days per year.

Temperatures reach or exceed 80 °F (27 °C) on an average of only 21 and 23 days a year at downtown and SFO, respectively. The dry period of May to October is mild to warm, with the normal monthly mean temperature peaking in September at 62.7 °F (17.1 °C). The rainy period of November to April is slightly cooler, with the normal monthly mean temperature reaching its lowest in January at 51.3 °F (10.7 °C). On average, there are 73 rainy days a year, and annual precipitation averages 23.65 inches (601 mm). Variation in precipitation from year to year is high. In 2013, a record low 5.59 in (142 mm) of rainfall was recorded at downtown San Francisco, where records have been kept since 1849; low records were shattered in much of the state. Snowfall in the city is very rare, with only 10 measurable accumulations recorded since 1852, most recently in 1976 when up to 5 inches (130 mm) fell on Twin Peaks.

The highest recorded temperature at the official National Weather Service office was 103 °F (39 °C) on July 17, 1988, and June 14, 2000. The lowest recorded temperature was 27 °F (âˆ'3 °C) on December 11, 1932. The National Weather Service provides a helpful visual aid graphing the information in the table below to display visually by month the annual typical temperatures, the past year's temperatures, and record temperatures.

San Francisco falls under the USDA 10b Plant Hardiness zone.

Demographics

The 2010 United States Census reported that San Francisco had a population of 805,235. With a population density of 17,160 per square mile (6,632/km2), San Francisco is the second-most densely populated major American city (among cities greater than 200,000 population).

San Francisco is the traditional focal point of the San Francisco Bay Area and forms part of the five-county San Franciscoâ€"Oaklandâ€"Fremont, CA Metropolitan Statistical Area, a region of 4.5 million people. It is also classified as part of the greater 12-county San Jose-San Francisco-Oakland, CA Combined Statistical Area, whose population is over 8.4 million, making it the fifth-largest in the United States as of 2013. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates San Francisco's population increased to 837,442 as of July 2013.

Race and ethnicity

As of the 2010 census, the ethnic makeup and population of San Francisco included: 390,387 Whites (48.1%), 267,915 Asians (33.3%), 48,870 African Americans (6.1%), 4,024 Native Americans (0.5%), 3,359 Pacific Islanders (0.4%), 53,021 from other races (6.6%), and 37,659 from two or more races (4.7%). There were 121,744 Hispanics or Latinos of any race (15.1%).

San Francisco has a minority-majority population, as non-Hispanic whites comprise less than half of the population, 41.9%, down from 92.5% in 1940. The principal Hispanic groups in the city were those of Mexican (7.4%), Salvadoran (2.0%), Nicaraguan (0.9%), Guatemalan (0.8%), and Puerto Rican (0.5%), ancestry. The Hispanic population is most heavily concentrated in the Mission District, Tenderloin District, and Excelsior District. San Francisco's African American population has declined in recent decades, from 13.4% of the population in 1970 to 6.1%. The current percentage of African Americans in San Francisco is similar to that of the state of California; conversely, the city's percentage of Hispanic residents is less than half of that of the state. The majority of the city's black population reside within the neighborhoods of Bayview-Hunters Point, and Visitacion Valley in southeastern San Francisco, and in the Fillmore District in the northeastern part of the city.

In 2010, residents of Chinese ethnicity constituted the largest single ethnic minority group in San Francisco at 21.4% of the population; the other Asian groups are Filipinos (4.5%), Vietnamese (1.6%), Japanese (1.3%), Asian Indians (1.2%), Koreans (1.2%), Thais (0.3%), Burmese (0.2%), Cambodians (0.2%), and Indonesians, Laotians, and Mongolians make up less than 0.1% of the city's population. The population of Chinese ancestry is most heavily concentrated in Chinatown, Sunset District, and Richmond District, whereas Filipinos are most concentrated in the Crocker-Amazon (which is continuous with the Filipino community of Daly City, the city with one of the highest concentrations of Filipinos in North America), as well as in SoMa.

After declining in the 1970s and 1980s, the Filipino community in the city has experienced a significant resurgence. The San Francisco Bay Area is home to over 382,950 Filipino Americans, one of the largest communities of Filipinos outside of the Philippines. The Tenderloin District is home to a large portion of the city's Vietnamese population as well as businesses and restaurants, which is known as the city's Little Saigon. Koreans and Japanese have a large presence in the Western Addition, which is where the city's Japantown is located. The Pacific Islander population is 0.4% (0.8% including those with partial ancestry). Over half of the Pacific Islander population is of Samoan descent, with residence in the Bayview-Hunters Point and Visitacion Valley areas; Pacific Islanders make up more than three percent of the population in both communities.

Native-born Californians form a relatively small percentage of the city's population: only 37.7% of its residents were born in California, while 25.2% were born in a different U.S. state. More than a third of city residents (35.6%) were born outside the United States.

Education, households, and income

Of all major cities, San Francisco has the second-highest percentage of residents with a college degree, behind only Seattle. Over 44% of adults within the city limits have a bachelor's or higher degree. USA Today reported that Rob Pitingolo, a researcher who measured college graduates per square mile, found that San Francisco had the highest rate at 7,031 per square mile, or over 344,000 total graduates in the city's 46.7 square miles (121Â km2).

The Census reported that 780,971 people (97.0% of the population) lived in households, 18,902 (2.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 5,362 (0.7%) were institutionalized. There were 345,811 households, out of which 63,577 (18.4%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 109,437 (31.6%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 28,844 (8.3%) had a female householder with no spouse present, 12,748 (3.7%) had a male householder with no spouse present. There were 21,677 (6.3%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 10,384 (3.0%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 133,366 households (38.6%) were made up of individuals and 34,234 (9.9%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26. There were 151,029 families (43.7% of all households); the average family size was 3.11. There were 376,942 housing units, at an average density of 1,625.5 per square mile (627.6/km2), of which 123,646 (35.8%) were owner-occupied, and 222,165 (64.2%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.3%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.4%. 327,985 people (40.7% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 452,986 people (56.3%) lived in rental housing units.

According to the 2005 American Community Survey, San Francisco has the highest percentage of gay and lesbian individuals of any of the 50 largest U.S. cities, at 15.4%. San Francisco also has the highest percentage of same-sex households of any American county, with the Bay Area having a higher concentration than any other metropolitan area.

San Francisco ranks third of American cities in median household income with a 2007 value of $65,519. Median family income is $81,136, and San Francisco ranks 8th of major cities worldwide in the number of billionaires known to be living within city limits. Following a national trend, an emigration of middle-class families is contributing to widening income disparity and has left the city with a lower proportion of children, 14.5%, than any other large American city.

The city's poverty rate is 11.8% and the number of families in poverty stands at 7.4%, both lower than the national average. The unemployment rate stands at 5.3% as of January 2014. Homelessness has been a chronic and controversial problem for San Francisco since the early 1970s when many mentally ill patients were deinstitutionalized, due to changes which began during the 1960s with the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid. The homeless population is estimated to be 13,500 with 6,500 living on the streets. The city is believed to have the highest number of homeless inhabitants per capita of any major U.S. city. Rates of reported violent and property crimes for 2009 (736 and 4,262 incidents per 100,000 residents, respectively) are slightly lower than for similarly sized U.S. cities.

Languages and ages

As of 2010, 54.58% (411,728) of San Francisco residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 18.60% (140,302) spoke Chinese, 11.68% (88,147) Spanish, 3.42% (25,767) Tagalog, 1.86% (14,017) Russian, 1.45% (10,939) Vietnamese, 1.05% (7,895) French, 0.90% (6,777) Japanese, 0.88% (6,624) Korean, 0.56% (4,215) German, 0.53% (3,995) Italian, and Pacific Islander languages were spoken as a main language by 0.47% (3,535) of the population over the age of five. In total, 45.42% (342,693) of San Francisco's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.

The age distribution of the city was as follows: 107,524 people (13.4%) under the age of 18, 77,664 people (9.6%) aged 18 to 24, 301,802 people (37.5%) aged 25 to 44, 208,403 people (25.9%) aged 45 to 64, and 109,842 people (13.6%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.5 years. For every 100 females there were 102.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 102.8 males.

Economy

San Francisco has a diversified service economy, with employment spread across a wide range of professional services, including financial services, tourism, and (increasingly) high technology. In 2012, approximately 25% of workers were employed in professional business services; 16% in government services; 15% in leisure and hospitality; 11% in education and health care; and 9% in financial activities. In 2013, GDP in the five-county San Francisco metropolitan area was US$388.3 billion.

The legacy of the California Gold Rush turned San Francisco into the principal banking and finance center of the West Coast in the early twentieth century. Montgomery Street in the Financial District became known as the "Wall Street of the West", home to the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the Wells Fargo corporate headquarters, and the site of the now-defunct Pacific Coast Stock Exchange. Bank of America, a pioneer in making banking services accessible to the middle class, was founded in San Francisco and in the 1960s, built the landmark modern skyscraper at 555 California Street for its corporate headquarters. Many large financial institutions, multinational banks, and venture capital firms are based in or have regional headquarters in the city. With over 30 international financial institutions, six Fortune 500 companies, and a large support infrastructure of professional servicesâ€"including law, public relations, architecture and designâ€"San Francisco is designated as an Alpha(-) World City, and is ranked in 10th place among the top global financial centers.

Tourism is one of the city's largest private-sector industries, accounting for more than one out of seven jobs in the city. The city's frequent portrayal in music, film, and popular culture has made the city and its landmarks recognizable worldwide. San Francisco attracts the fifth-highest number of foreign tourists of any city in the U.S. and ranks 43rd out of the 100 most visited cities worldwide according to Euromonitor International. More than 16.9Â million visitors arrived in San Francisco in 2013, injecting US$9.4Â billion into the economy. With a large hotel infrastructure and a world-class convention facility in the Moscone Center, San Francisco is a popular destination for annual conventions and conferences.

Since the 1990s, San Francisco's economy has diversified away from finance and tourism towards the growing fields of high tech, biotechnology, and medical research. Technology jobs accounted for just 1 percent of San Francisco's economy in 1990, growing to 4 percent in 2010 and an estimated 8 percent by the end of 2013. San Francisco became an epicenter of Internet start-up companies during the dot-com bubble of the 1990s and the subsequent social media boom of the late 2000s. Since 2010, San Francisco proper has attracted an increasing share of venture capital investments as compared to nearby Silicon Valley, attracting 423 financings worth US$4.58 billion in 2013. In 2004, the city approved a payroll tax exemption for biotechnology companies to foster growth in the Mission Bay neighborhood, site of a second campus and hospital of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Mission Bay hosts the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences, and Gladstone Institutes, as well as more than 40 private-sector life sciences companies.

The top employer in the city is the city government itself, employing 5.3% (25,000+ people) of the city's population, followed by UCSF with over 22,000 employees. Thirdâ€"at 1.8% (8,500+ people)â€"is California Pacific Medical Center, the largest private-sector employer. Small businesses with fewer than 10 employees and self-employed firms make up 85% of city establishments, and the number of San Franciscans employed by firms of more than 1,000 employees has fallen by half since 1977. The growth of national big box and formula retail chains into the city has been made intentionally difficult by political and civic consensus. In an effort to buoy small privately owned businesses in San Francisco and preserve the unique retail personality of the city, the Small Business Commission supports a publicity campaign to keep a larger share of retail dollars in the local economy, and the Board of Supervisors has used the planning code to limit the neighborhoods where formula retail establishments can set up shop, an effort affirmed by San Francisco voters.

Like many U.S. cities, San Francisco once had a significant manufacturing sector employing nearly 60,000 workers in 1969, but nearly all production left for cheaper locations by the 1980s. As of 2014, San Francisco has seen a small resurgence in manufacturing, with more than 4,000 manufacturing jobs across 500 companies, doubling since 2011. The city's largest manufacturing employer is Anchor Brewing Company, and the largest by revenue is Timbuk2.

Culture and contemporary life

Although the Financial District, Union Square, and Fisherman's Wharf are well-known around the world, San Francisco is also characterized by its numerous culturally rich streetscapes featuring mixed-use neighborhoods anchored around central commercial corridors to which residents and visitors alike can walk. Because of these characteristics, San Francisco is ranked the second "most walkable" city in the U.S. by Walkscore.com. Many neighborhoods feature a mix of businesses, restaurants and venues that cater to both the daily needs of local residents while also serving many visitors and tourists. Some neighborhoods are dotted with boutiques, cafes and nightlife such as Union Street in Cow Hollow, 24th Street in Noe Valley, Valencia Street in the Mission, and Irving Street in the Inner Sunset. This approach especially has influenced the continuing South of Market neighborhood redevelopment with businesses and neighborhood services rising alongside high-rise residences.

Since the 1990s, the demand for skilled information technology workers from local startups and nearby Silicon Valley has attracted white-collar workers from all over the world and created a high standard of living in San Francisco. Many neighborhoods that were once blue-collar, middle, and lower class have been gentrifying, as many of the city's traditional business and industrial districts have experienced a renaissance driven by the redevelopment of the Embarcadero, including the neighborhoods South Beach and Mission Bay. The city's property values and household income have risen to among the highest in the nation, creating a large and upscale restaurant, retail, and entertainment scene. According to a 2008 quality of life survey of global cities, San Francisco has the second highest quality of living of any U.S. city. However, due to the exceptionally high cost of living, many of the city's middle and lower-class families have been leaving the city for the outer suburbs of the Bay Area, or for California's Central Valley.

The international character that San Francisco has enjoyed since its founding is continued today by large numbers of immigrants from Asia and Latin America. With 39% of its residents born overseas, San Francisco has numerous neighborhoods filled with businesses and civic institutions catering to new arrivals. In particular, the arrival of many ethnic Chinese, which accelerated beginning in the 1970s, has complemented the long-established community historically based in Chinatown throughout the city and has transformed the annual Chinese New Year Parade into the largest event of its kind outside China.

With the arrival of the "beat" writers and artists of the 1950s and societal changes culminating in the Summer of Love in the Haight-Ashbury district during the 1960s, San Francisco became a center of liberal activism and of the counterculture that arose at that time. The Democrats and to a lesser extent the Green Party have dominated city politics since the late 1970s, after the last serious Republican challenger for city office lost the 1975 mayoral election by a narrow margin. San Francisco has not voted more than 20% for a Republican presidential or senatorial candidate since 1988. In 2007, the city expanded its Medicaid and other indigent medical programs into the "Healthy San Francisco" program, which subsidizes certain medical services for eligible residents.

San Francisco has long had an LGBT-friendly history. It was home to the first lesbian-rights organization in the United States, Daughters of Bilitis; the first openly gay person to run for public office in the U.S., José Sarria; the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in the U.S., Harvey Milk; the first openly lesbian judge appointed in the U.S., Mary C. Morgan; and the first transgender police commissioner, Theresa Sparks. The city's large gay population has created and sustained a politically and culturally active community over many decades, developing a powerful presence in San Francisco's civic life. One of the most popular destinations for gay tourists internationally, the city hosts San Francisco Pride, one of the largest and oldest pride parades.

San Francisco also has had a very active environmental community. Starting with the founding of the Sierra Club in 1892 to the establishment of the non-profit Friends of the Urban Forest in 1981, San Francisco has been at the forefront of many global discussions regarding our natural environment. The 1980 San Francisco Recycling Program was one of the earliest curbside recycling programs. The city's GoSolarSF incentive promotes solar installations and the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission is rolling out the CleanPowerSF program to sell electricity from local renewable sources. SF Greasecycle is a program to recycle used cooking oil for conversion to biodiesel.

The newly completed Sunset Reservoir Solar Project has installed 25,000 solar panels on the 480,000 sq ft (45,000 m2) roof of the reservoir. The 5-megawatt plant more than tripled the city's 2-megawatt solar generation capacity when it opened in December 2010.

Entertainment and performing arts

San Francisco's War Memorial and Performing Arts Center hosts some of the most enduring performing-arts companies in the U.S. The War Memorial Opera House houses the San Francisco Opera, the second-largest opera company in North America as well as the San Francisco Ballet, while the San Francisco Symphony plays in Davies Symphony Hall. The Herbst Theatre stages an eclectic mix of music performances, as well as public radio's City Arts & Lectures.

The Fillmore is a music venue located in the Western Addition. It is the second incarnation of the historic venue that gained fame in the 1960s under concert promoter Bill Graham, housing the stage where now-famous musicians such as the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Led Zeppelin and Jefferson Airplane first performed, fostering the San Francisco Sound. Beach Blanket Babylon is a zany musical revue and a civic institution that has performed to sold-out crowds in North Beach since 1974.

Comedian and actor, Robin Williams helped San Francisco become recognized as a good town for comedy clubs. He rose to fame, having gotten his early start in San Francisco clubs such as the Holy City Zoo, the Punchline and the Other Cafe in the '70's. He also shot seven films on location in San Francisco.

The American Conservatory Theater (A.C.T.) has been a force in Bay Area performing arts since its arrival in San Francisco in 1967, regularly staging productions. San Francisco frequently hosts national touring productions of Broadway theatre shows in a number of vintage 1920s-era venues in the Theater District including the Curran, Orpheum, and Golden Gate Theatres.

Museums

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) houses 20th century and contemporary works of art. It moved to its current building in the South of Market neighborhood in 1995 and now attracts more than 600,000 visitors annually. The Palace of the Legion of Honor holds primarily European antiquities and works of art at its Lincoln Park building modeled after its Parisian namesake. It is administered by Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, which also operates the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park. The de Young's collection features American decorative pieces and anthropological holdings from Africa, Oceania and the Americas. Prior to construction of its current copper-clad structure, completed in 2005, the de Young also housed the Asian Art Museum, which, with artifacts from over 6,000Â years of history across Asia, moved into the former public library next to Civic Center in 2003.

Opposite the Music Concourse from the de Young stands the California Academy of Sciences, a natural history museum that also hosts the Morrison Planetarium and Steinhart Aquarium. Its current structure, featuring a living roof, is an example of sustainable architecture and opened in 2008. Located on Pier 15 on the Embarcadero, the Exploratorium is an interactive science museum founded by physicist Frank Oppenheimer in 1969. Two museum ships are moored near Fisherman's Wharf, the SS Jeremiah O'Brien Liberty ship and USS Pampanito submarine. On Nob Hill, the Cable Car Museum is a working museum featuring the cable car power house, which drives the cables, and the car depot.

Sports and recreation

Major League Baseball's San Francisco Giants left New York for California prior to the 1958 season. Though boasting such stars as Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Barry Bonds, the club went 52 years until its first World Series title in 2010, and won two additional titles in 2012 and in 2014. The Giants play at AT&T Park, which opened in 2000, a cornerstone project of the South Beach and Mission Bay redevelopment. In 2012, San Francisco was ranked #1 among America's Best Baseball cities. The study examined which U.S. metro areas have produced the most Major Leaguers since 1920.

The San Francisco 49ers of the National Football League (NFL) were the longest-tenured major professional sports franchise in the city. The team began play in 1946 as an All-America Football Conference (AAFC) league charter member, moved to the NFL in 1950 and into Candlestick Park in 1971. The team began playing its home games at Levi's Stadium in Santa Clara, California in 2014; the team is still named the "San Francisco 49ers", even though they are much closer to the city of San Jose. The 49ers have won five Super Bowl titles in the 1980s and 1990s behind coaches Bill Walsh and George Seifert, and stars such as Joe Montana, Steve Young, Ronnie Lott, and Jerry Rice.

At the collegiate level, the Dons of the University of San Francisco compete in NCAA Division I, where Bill Russell guided the program to basketball championships in 1955 and 1956. The San Francisco State Gators and the Academy of Art University Urban Knights compete in Division II. AT&T Park has since 2002 hosted an annual post-season college football bowl game, currently named the Fight Hunger Bowl. In 2011, San Francisco hosted the California Golden Bears football team at Candlestick Park and AT&T Park while their home stadium in Berkeley was being renovated.

The Bay to Breakers footrace, held annually since 1912, is best known for colorful costumes and a celebratory community spirit. The San Francisco Marathon attracts more than 21,000 participants. The Escape from Alcatraz triathlon has, since 1980, attracted 2,000 top professional and amateur triathletes for its annual race. The Olympic Club, founded in 1860, is the oldest athletic club in the United States. Its private golf course, situated on the border with Daly City, has hosted the U.S. Open on five occasions. The public Harding Park Golf Course is an occasional stop on the PGA Tour. San Francisco hosted the 2013 America's Cup yacht racing competition.

With an ideal climate for outdoor activities, San Francisco has ample resources and opportunities for amateur and participatory sports and recreation. There are more than 200 miles (320Â km) of bicycle paths, lanes and bike routes in the city, and the Embarcadero and Marina Green are favored sites for skateboarding. Extensive public tennis facilities are available in Golden Gate Park and Dolores Park, as well as at smaller neighborhood courts throughout the city. San Francisco residents have often ranked among the fittest in the U.S.

Boating, sailing, windsurfing and kitesurfing are among the popular activities on San Francisco Bay, and the city maintains a yacht harbor in the Marina District. The St. Francis Yacht Club and Golden Gate Yacht Club are located in the Marina Harbor. The South Beach Yacht Club is located next to AT&T Park and Pier 39 has an extensive marina.

Historic Aquatic Park located along the northern San Francisco shore hosts two swimming and rowing clubs. The South End Rowing Club, established in 1873, and the Dolphin Club maintain a friendly rivalry between members. Swimmers can be seen daily braving the typically cold bay waters.

Cycling is growing in San Francisco. Annual bicycle counts conducted by the Municipal Transportation Agency (MTA) in 2010 showed the number of cyclists at 33 locations had increased 58% from the 2006 baseline counts. The MTA estimates that about 128,000 trips are made by bicycle each day in the city, or 6% of total trips. Improvements in cycling infrastructure in recent years, including additional bike lanes and parking racks, has made cycling in San Francisco safer and more convenient. Since 2006, San Francisco has received a Bicycle Friendly Community status of "Gold" from the League of American Bicyclists.

Beaches and parks

Several of San Francisco's parks and nearly all of its beaches form part of the regional Golden Gate National Recreation Area, one of the most visited units of the National Park system in the United States with over 13 million visitors a year. Among the GGNRA's attractions within the city are Ocean Beach, which runs along the Pacific Ocean shoreline and is frequented by a vibrant surfing community, and Baker Beach, which is located in a cove west of the Golden Gate and part of the Presidio, a former military base. Also within the Presidio is Crissy Field, a former airfield that was restored to its natural salt marsh ecosystem. The GGNRA also administers Fort Funston, Lands End, Fort Mason, and Alcatraz. The National Park Service separately administers the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park â€" a fleet of historic ships and waterfront property around Aquatic Park.

There are more than 220 parks maintained by the San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department. The largest and best-known city park is Golden Gate Park, which stretches from the center of the city west to the Pacific Ocean. Once covered in native grasses and sand dunes, the park was conceived in the 1860s and was created by the extensive planting of thousands of non-native trees and plants. The large park is rich with cultural and natural attractions such as the Conservatory of Flowers, Japanese Tea Garden and San Francisco Botanical Garden. Lake Merced is a fresh-water lake surrounded by parkland and near the San Francisco Zoo, a city-owned park that houses more than 250 animal species, many of which are endangered. The only park managed by the California State Park system located principally in San Francisco, Candlestick Point was the state's first urban recreation area.

Law and government

San Franciscoâ€"officially known as the City and County of San Franciscoâ€"is a consolidated city-county, a status it has held since the 1856 secession of what is now San Mateo County. It is the only such consolidation in California. The mayor is also the county executive, and the county Board of Supervisors acts as the city council. The government of San Francisco is a charter city and is constituted of two co-equal branches. The executive branch is headed by the mayor and includes other citywide elected and appointed officials as well as the civil service. The 11-member Board of Supervisors, the legislative branch, is headed by a president and is responsible for passing laws and budgets, though San Franciscans also make use of direct ballot initiatives to pass legislation.

The members of the Board of Supervisors are elected as representatives of specific districts within the city. Upon the death or resignation of mayor, the President of the Board of Supervisors becomes acting mayor until the full Board elects an interim replacement for the remainder of the term. In 1978, Dianne Feinstein assumed the office following the assassination of George Moscone and was later selected by the Board to finish the term. In 2011, Edwin M. Lee was selected by the Board to finish the term of Gavin Newsom, who resigned to take office as Lieutenant Governor of California.

Because of its unique city-county status, local government exercises jurisdiction over property that would otherwise be located outside of its corporation limit. San Francisco International Airport, though located in San Mateo County, is owned and operated by the City and County of San Francisco. San Francisco also has a county jail complex located in San Mateo County, in an unincorporated area adjacent to San Bruno. San Francisco was also granted a perpetual leasehold over the Hetch Hetchy Valley and watershed in Yosemite National Park by the Raker Act in 1913.

San Francisco serves as the regional hub for many arms of the federal bureaucracy, including the U.S. Court of Appeals, the Federal Reserve Bank, and the U.S. Mint. Until decommissioning in the early 1990s, the city had major military installations at the Presidio, Treasure Island, and Hunters Pointâ€"a legacy still reflected in the annual celebration of Fleet Week. The State of California uses San Francisco as the home of the state supreme court and other state agencies. Foreign governments maintain more than seventy consulates in San Francisco.

The municipal budget for fiscal year 2013â€"14 was $7.9 billion. The city employs around 27,000 workers.

Crime and public safety

The following table includes the number of incidents reported and the rate per 1,000 persons for each type of offense.

In 2011, 50 murders were reported, which is 6.1 per 100,000 people. There were about 134 rapes, 3,142 robberies, and about 2,139 assaults. There were about 4,469 burglaries, 25,100 thefts, and 4,210 motor vehicle thefts. The Tenderloin area has the highest crime rate in San Francisco: 70% of the city's violent crimes, and around one-fourth of the city's murders, occur in this neighborhood. The Tenderloin also sees high rates of homelessness, drug abuse, gang violence, and prostitution. Another area with high crime rates is the Bayview-Hunters Point area. Homelessness is also a growing problem in the city.

Several street gangs operate in the city, including MS-13, the Sureños and Norteños in the Mission District, and to some extent the Crips in Bayview â€" Hunters-Point. There is a presence of Asian gangs in Chinatown. In 1977, an ongoing rivalry between two Chinese gangs led to a shooting attack at a restaurant in Chinatown, which left 5 people dead and 11 wounded. None of the victims in this attack were gang members. Five members of the Joe Boys gang were arrested and convicted of the crime. In 1990, a gang-related shooting killed one man and wounded six others outside a nightclub near Chinatown. In 1998, six teenagers were shot and wounded at the Chinese Playground; a 16-year-old boy was subsequently arrested.

The city is mainly patrolled by the San Francisco Police Department. The San Francisco Sheriff's Department, BART Police (public transit only), Amtrak Police, California Highway Patrol and many other local, state, and federal agencies perform law enforcement tasks in the city.

The San Francisco Fire Department provides both fire suppression and emergency medical services to the city.

Education

Colleges and universities

The University of California, San Francisco is the sole campus of the University of California system entirely dedicated to graduate education in health and biomedical sciences. It is ranked among the top-five medical schools in the United States and operates the UCSF Medical Center, which ranks among the top 15 hospitals in the country. UCSF is a major local employer, second in size only to the city and county government. A 43-acre (170,000Â m2) Mission Bay campus was opened in 2003, complementing its original facility in Parnassus Heights. It contains research space and facilities to foster biotechnology and life sciences entrepreneurship and will double the size of UCSF's research enterprise. All in all, UCSF operates 20 facilities across San Francisco. The University of California, Hastings College of the Law, founded in Civic Center in 1878, is the oldest law school in California and claims more judges on the state bench than any other institution. San Francisco's two University of California institutions have recently formed an official affiliation in the UCSF/UC Hastings Consortium on Law, Science & Health Policy.

San Francisco State University is part of the California State University system and is located near Lake Merced. The school has approximately 30,000 students and awards undergraduate, master's and doctoral degrees in more than 100 disciplines. The City College of San Francisco, with its main facility in the Ingleside district, is one of the largest two-year community colleges in the country. It has an enrollment of about 100,000 students and offers an extensive continuing education program.

Founded in 1855, the University of San Francisco, a private Jesuit university located on Lone Mountain, is the oldest institution of higher education in San Francisco and one of the oldest universities established west of the Mississippi River. Golden Gate University is a private, nonsectarian, coeducational university formed in 1901 and located in the Financial District. It is primarily a post-graduate institution focused on professional training in law and business, with smaller undergraduate programs linked to its graduate and professional schools.

With an enrollment of 13,000 students, the Academy of Art University is the largest institute of art and design in the nation. Founded in 1871, the San Francisco Art Institute is the oldest art school west of the Mississippi. The California College of the Arts, located north of Potrero Hill, has programs in architecture, fine arts, design, and writing. The San Francisco Conservatory of Music, the only independent music school on the West Coast, grants degrees in orchestral instruments, chamber music, composition, and conducting. The California Culinary Academy, associated with the Le Cordon Bleu program, offers programs in the culinary arts, baking and pastry arts, and hospitality and restaurant management. California Institute of Integral Studies, founded in 1968, offers a variety of graduate programs in its Schools of Professional Psychology & Health, and Consciousness and Transformation. Known for combining spirituality and social change, the Institute also features a bachelor's degree completion program.

Primary and secondary schools

Public schools are run by the San Francisco Unified School District as well as the State Board of Education for some charter schools. Lowell High School, the oldest public high school in the U.S. west of the Mississippi, and the smaller School of the Arts High School are two of San Francisco's magnet schools at the secondary level. Just under 30% of the city's school-age population attends one of San Francisco's more than 100 private or parochial schools, compared to a 10% rate nationwide. Nearly 40 of those schools are Catholic schools managed by the Archdiocese of San Francisco.

Media

The major daily newspaper in San Francisco is the San Francisco Chronicle, which is currently Northern California's most widely circulated newspaper. The Chronicle is most famous for a former columnist, the late Herb Caen, whose daily musings attracted critical acclaim and represented the "voice of San Francisco". The San Francisco Examiner, once the cornerstone of William Randolph Hearst's media empire and the home of Ambrose Bierce, declined in circulation over the years and now takes the form of a free daily tabloid, under new ownership. Sing Tao Daily claims to be the largest of several Chinese language dailies that serve the Bay Area. Alternative weekly newspapers include the San Francisco Bay Guardian and SFÂ Weekly. San Francisco Magazine and 7x7 are major glossy magazines about San Francisco. The national newsmagazine Mother Jones is also based in San Francisco.

The San Francisco Bay Area is the sixth-largest TVÂ market and the fourth-largest radio market in the U.S. The city's oldest radio station, KCBS (AM), began as an experimental station in San Jose in 1909, before the beginning of commercial broadcasting. KALW was the city's first FM radio station when it signed on the air in 1941. The city's first television station was KPIX, which began broadcasting in 1948.

All major U.S. television networks have affiliates serving the region, with most of them based in the city. CNN, MSNBC, BBC, Al Jazeera America, Russia Today, and CCTV America also have regional news bureaus in San Francisco. Bloomberg West was launched in 2011 from a studio on the Embarcadero. ESPN uses the local ABC studio for their broadcasting. The regional sports network, Comcast SportsNet Bay Area and it's sister station Comcast SportsNet California, are both located in San Francisco. The Pac-12 Network is also based in San Francisco.

Public broadcasting outlets include both a television station and a radio station, both broadcasting under the call letters KQED from a facility near the Potrero Hill neighborhood. KQED-FM is the most-listened-to National Public Radio affiliate in the country. San Franciscoâ€"based CNET and Salon.com pioneered the use of the Internet as a media outlet. Satellite channel non-commercial Link TV was launched in 1999 from San Francisco.

San Francisco inventors have made significant marks on modern media. In 1877 Eadweard Muybridge pioneered work in photographic studies of motion and in motion-picture projection from. These were the first motion pictures. Then in 1927, Philo Farnsworth's image dissector camera tube transmitted its first image. This was the first television.

Transportation

Freeways and roads

Due to its unique geography, and the freeway revolts of the late 1950s, San Francisco is one of the few American cities with arterial thoroughfares instead of having numerous highways within the city.

Interstate 80 begins at the approach to the Bay Bridge and is the only direct automobile link to the East Bay. U.S. Route 101 connects to the western terminus of Interstate 80 and provides access to the south of the city along San Francisco Bay toward Silicon Valley. Northbound, the routing for U.S. 101 uses arterial streets Mission Street, Van Ness Avenue, Lombard Street, Richardson Avenue, and Doyle Drive to connect to the Golden Gate Bridge, the only direct automobile link to Marin County and the North Bay.

State Route 1 also enters San Francisco from the north via the Golden Gate Bridge, but turns south away from the routing of U.S. 101, first onto Park Presidio Blvd through Golden Gate Park, and then bisecting the west side of the city as the 19th Avenue arterial thoroughfare, joining with Interstate 280 at the city's southern border. Interstate 280 continues this southerly routing along the central portion of the Peninsula south to San Jose. Interstate 280 also turns to the east along the southern edge of the city, terminating just south of the Bay Bridge in the South of Market neighborhood. After the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, city leaders decided to demolish the Embarcadero Freeway as well, and voters approved demolition of a portion of the Central Freeway, converting them into street-level boulevards.

State Route 35, which traverses the majority of the Peninsula along the ridge of the Santa Cruz Mountains, enters the city from the south as Skyline Boulevard, following city streets until it terminates at its intersection with Highway 1. State Route 82 enters San Francisco from the south as Mission Street, following the path of the historic El Camino Real and terminating shortly thereafter at its junction with 280. Major eastâ€"west thoroughfares include Geary Boulevard, the Lincoln Way/Fell Street corridor, and Market Street/Portola Drive.

The Western Terminus of the historic transcontinental Lincoln Highway, the first road across America, is in San Francisco's Lincoln Park.

Public transportation

32% of San Francisco residents use public transportation in daily commuting to work, ranking it first on the West Coast and third overall in the United States. The San Francisco Municipal Railway, known as Muni, is the primary public transit system of San Francisco. Muni is the seventh-largest transit system in the United States, with 210,848,310 rides in 2006. The system operates both a combined light rail and subway system, the Muni Metro, and a large bus network. Additionally, it runs a historic streetcar line, which runs on Market Street from Castro Street to Fisherman's Wharf. It also operates the famous cable cars, which have been designated as a National Historic Landmark and are a major tourist attraction.

Bay Area Rapid Transit, a regional Commuter Rail system, connects San Francisco with the East Bay through the underwater Transbay Tube. The line runs under Market Street to Civic Center where it turns south to the Mission District, the southern part of the city, and through northern San Mateo County, to the San Francisco International Airport, and Millbrae. Another Commuter Rail system, Caltrain, runs from San Francisco along the San Francisco Peninsula to San Jose. Historically, trains operated by Southern Pacific Lines ran from San Francisco to Los Angeles, via Palo Alto and San Jose.

The Transbay Terminal serves as the terminus for long-range bus service (such as Greyhound) and as a hub for regional bus systems AC Transit (Alameda & Contra Costa counties), WestCAT, SamTrans (San Mateo County), and Golden Gate Transit (Marin and Sonoma Counties).

Amtrak California Thruway Motorcoach runs a shuttle bus from San Francisco to its rail station across the Bay in Emeryville. Lines from Emeryville Station include the Capitol Corridor, San Joaquin, California Zephyr, and Coast Starlight. Thruway service also runs south to San Luis Obispo, California with connection to the Pacific Surfliner.

Megabus recently relaunched intercity bus service in California and Nevada. San Francisco riders can chose from three routes (SF-San Jose-LA, SF-Oakland-LA, & SF-Sacramento-Reno). The San Francisco stop is located in front of the Caltrain Station. BoltBus began service between the Bay Area and Los Angeles in October 2013.

San Francisco Bay Ferry operates from the Ferry Building and Pier 39 to points in Oakland, Alameda, Bay Farm Island, South San Francisco, and north to Vallejo in Solano County. The Golden Gate Ferry is the other ferry operator with service between San Francisco and Marin County. Soltrans runs supplemental bus service between the Ferry Building and Vallejo.

Cycling is a popular mode of transportation in San Francisco. 75,000 residents commute by bicycle per day.

Pedestrian traffic is a major mode of transport. In 2011, Walk Score ranked San Francisco the second-most walkable city in the United States.

San Francisco was an early adopter of carsharing in America. The non profit City Carshare opened in 2001. Zipcar closely followed.

Bay Area Bike Share launched in August 2013 with 700 bikes in downtown San Francisco and selected cities south to San Jose. The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency and Bay Area Air Quality Management District are responsible for the operation with management provided by Alta Bicycle Share. The system will be expanded in the future.

Airports

Though located 13 miles (21Â km) south of downtown in unincorporated San Mateo County, San Francisco International Airport (SFO) is under the jurisdiction of the City and County of San Francisco. SFO is a hub for United Airlines and Virgin America. SFO is a major international gateway to Asia and Europe, with the largest international terminal in North America. In 2011, SFO was the 8th busiest airport in the U.S. and 22nd busiest in the world, handling over 40.9Â million passengers.

Located across the bay, Oakland International Airport is a popular, low-cost alternative to SFO. Geographically, Oakland Airport is approximately the same distance from downtown San Francisco as SFO, but due to its location across San Francisco Bay, it is greater driving distance from San Francisco.

Seaports

The Port of San Francisco was once the largest and busiest seaport on the West Coast. It featured rows of piers perpendicular to the shore, where cargo from the moored ships was handled by cranes and manual labor and transported to nearby warehouses. The port handled cargo to and from trans-Pacific and Atlantic destinations, and was the West Coast center of the lumber trade. The 1934 West Coast Longshore Strike, an important episode in the history of the American labor movement, brought most ports to a standstill. The advent of container shipping made pier-based ports obsolete, and most commercial berths moved to the Port of Oakland and Port of Richmond. A few active berths specializing in break bulk cargo remain alongside the Islais Creek Channel.

Many piers remained derelict for years until the demolition of the Embarcadero Freeway reopened the downtown waterfront, allowing for redevelopment. The centerpiece of the port, the Ferry Building, while still receiving commuter ferry traffic, has been restored and redeveloped as a gourmet marketplace. The port's other activities now focus on developing waterside assets to support recreation and tourism.

The port currently uses Pier 35 to handle the 60â€"80 cruise ship calls and 200,000 passengers that come to San Francisco. Itineraries from San Francisco usually include round trip cruises to Alaska and Mexico. The new James R. Herman Cruise Terminal Project at Pier 27 is scheduled to open 2014 as a replacement. The existing primary terminal at Pier 35 has neither the sufficient capacity to allow for the increasing length and passenger capacity of new cruise ships nor the amenities needed for an international cruise terminal.

On March 16, 2013, Princess Cruises Grand Princess became the first ship to home port in San Francisco year round. The ship offers cruises to Alaska, California Coasts, Hawaii, and Mexico. Grand Princess will be stationed in San Francisco until April 2014. Princess will also operate other ships during the summer of 2014, making it the only cruise line home porting year round in San Francisco.

Safety

San Francisco has significantly higher rates of pedestrian and bicyclist traffic deaths than the USA on average. In 2013, 21 pedestrians were killed in vehicle collisions, the highest since 2001, which is 2.5 deaths per 100,000 population â€" 70% higher than the national average of 1.5 deaths per 100,000 population. On January 14, 2014, Supervisor Jane Kim introduced Vision Zero, a proposal to eliminate all traffic fatalities in San Francisco by 2024.

Notable people

Consulates and sister cities

San Francisco participates in the Sister Cities program. A total of 41 consulates general and 23 honorary consulates have offices in the San Francisco Bay Area.